Dolphin sightseeing is one of the biggest draws to the Tampa Bay area. Visitors from around the world stop by John’s Pass for a cruise into the Boca Ciega Bay, hoping to catch a glimpse of the dolphins in the wild.

Many also hope to learn about these wonderful creatures, and who better to teach us than one of the most well-known animal behaviorists in Tampa Bay?

There is no greater authority than Dr. Weaver for expert insight into the local dolphin population. Her research vessel is a familiar sight to ship captains across Tampa Bay, where, for twenty years, she has studied bottlenose dolphin behavior. She brings expertise on the behavior of dolphins in Tampa Bay and the Florida coastal region and the factors affecting their movements. She has also developed a ‘dolphin dictionary’ to understand them better.

The persistent call of the dolphins has drawn her out to sea.

“The dolphins kept calling,” says Dr. Ann Weaver. “Several times in my life, I would be minding my own business when I received a phone call and was invited to study dolphins at some exotic location. Of course, I took the job!”

Let’s meet the dolphins of Tampa Bay with Dr. Weaver and explore the traits that set them apart and the dangers they face as a species.

Understanding the Dolphins of Tampa Bay

Getting to know a dolphin is no easy task. When Dr. Weaver began her quest to meet the dolphins in Tampa Bay in 2003, she brought experience from four other study sites and had a thorough knowledge of dolphin movements. This included an “ethogram,” a dictionary of dolphin behavior that she wrote and illustrated. It’s a catalog of behavior or activity based on an animal’s movements.

“When the dolphin surfaces, it’s doing something. We need a vocabulary to document what it is doing,” says Dr. Weaver. “It might be totally stressed out and staying at the surface, it might be curved in the letter C, it might be making noises; these are all different types of behavior. So I started by writing the ethogram.”

Dr. Weaver is no stranger to interpreting animal behavior in a language we can understand. Before working at sea, Dr. Weaver’s feet were planted firmly on the ground. Her first experience with wild bottlenose dolphins was off the southern California coast, where she earned her Master’s Degree from San Diego State University. It also introduced her to the challenging world of deciphering complex dolphin behavior.

The first step to deciphering dolphin behavior? Individual recognition.

“Even though I had trained myself to tell primates apart and could tell the 13 dolphins apart at SeaWorld after a while, it takes a long time to tell wild dolphins apart from a boat at sea,” says Dr. Weaver. “Without individual recognition, a solid study of complex behavior is impossible.”

Weaver likens telling 400 dolphins apart to watching the same actor in four hundred different TV shows, each starring its own dolphin.

“You never know what TV show is coming next, and you never know how long it’ll be between TV shows,” says Dr. Weaver. “They are usually swimming with different dolphins every time you see them,” adding that changing partners is part of the intricacy of dolphin behavior.

Dr. Weaver says it wasn’t until 2007 that she could reliably tell the dolphins in Tampa Bay apart. To get to her level of expertise, she says it took up to five days worth of analyzing photographs and data after every survey of her study area.

Notable Dolphins of Tampa Bay

Regular encounters with dolphins might mean coming into contact with familiar dorsal fins. Dr. Weaver notes that she has “extremely vivid relationships with a number of dolphins” and that some have stood out in her two decades’ worth of time studying our local population.

“In the beginning, you always have to give names to dolphins that don’t have gender,” says Dr. Weaver, who used letters of the alphabet because they were gender-neutral. “You can’t call them Mikey and Suzie because you’ll be wrong at least half the time.”

One bottlenose dolphin Dr. Weaver hopes to see again is known as Queen P.

Dolphins can live 50 years or more and, like people, may become clumsier with age. But not Queen P. She earned her nickname due to the regal way she conducts herself, says Dr. Weaver. “She conducts her affairs with a great deal of composure,” says Dr. Weaver. “She was bit on the head viciously by a shark, but she survived; a maritime miracle. She was also pregnant at the time, and she gave successful birth.”

Though she became familiar with Queen P, Dr. Weaver notes that she hasn’t seen her since January 2022. “I am anxious to find out what happened next, but she was one of the animals that was chased away by construction, and I haven’t seen her in a year,” she says.

Conservation and Being a Steward for the Bottlenose Dolphin

Dolphin sightseeing in Tampa Bay draws visitors year-round. The best time to see dolphins in Tampa Bay is fluid, considering that the local dolphin population isn’t as migratory as their Atlantic cousins. However, coastal construction and proposed dredging may drive the dolphins to search for a less turbulent home in the future.

However, Dr. Weaver says that people cannot assume that animals can cope. Within animal psychology, and with a few exceptions, an animal won’t think to move away from their habitat, even when it’s disturbed, she says.

“For people, if we don’t like it, we can move. Animals don’t think like that,” says Dr. Weaver. “They live in a place, learn how to live in it, and they stay there.”

Sustained disturbances, especially those that create underwater noise pollution, can drive even persistent dolphins to find a quieter place to live.

In 2006, construction began on a replacement for the John’s Pass Bridge and ended in 2011. To meet the dolphins that may have lived in John’s Pass before the start of the project, one may now need to seek them out elsewhere. Underwater drilling and pounding is an “acoustic nightmare” for dolphins and other marine life, says Dr. Weaver.

“If a dolphin mother cannot hear her calf, and her calf cannot hear her, this is dangerous,” Dr. Weaver claims. “A mother may not be able to hear her fish food either. She might shift to quieter waters.”

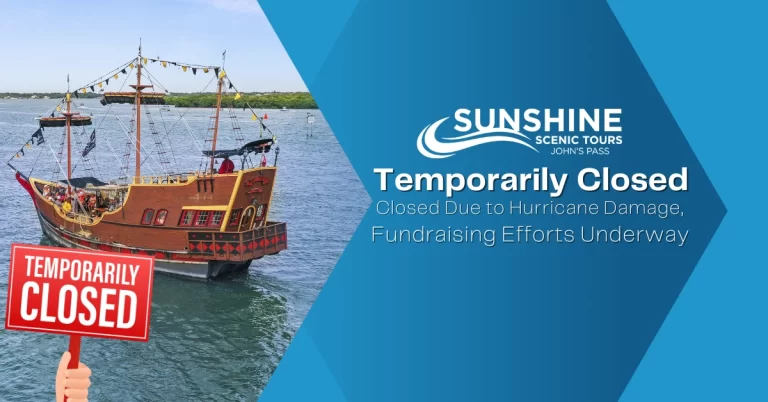

Tampa Bay dolphin tours rely on there being dolphins, of course. Dr. Weaver says tours such as those run by Sunshine Scenic Tours at Madeira Beach are “probably the best way to see local dolphins.” She refers to dolphins who have grown up around boats as urban dolphins, adding that they have probably been accustomed to touring boats for generations.

“Dolphins decide whether or not to be seen, and they are very good to us,” says Dr. Weaver. “You’re not going to do that with manatees, with shorebirds, or even local wildlife.”

Dr. Weaver names coastal construction as the driving factor behind dolphin flight. Generating political will to change practices and enact protections for local species may be as simple as having an opportunity to meet the dolphins up close.

“If somebody goes out, finds dolphins, and realizes that they love dolphins, maybe that will translate into positive behavior in the future,” says Dr. Weaver. She warns bluntly: “If we want our children to have dolphins for their children to see, we have to beat the drum now.”

Learn more about dolphins with us.

Understanding dolphins is one of the many things that will help us save them. Visit www.dolphinsdigital.org for more information on Dr. Weaver and her research on the bottlenose dolphins of Tampa Bay.

You may also see the dolphins of Tampa Bay aboard the Dolphin Quest, a John’s Pass dolphin cruise departing daily from John’s Pass at Madeira Beach, St. Petersburg.

Book a cruise and meet the dolphins of Tampa Bay today.